Maybe you’re like me and your interest in the natural world led you to permaculture design. Its message resonated and you wanted to learn more, you wanted to experiment. Or, maybe the term is entirely new and you’re thinking: “Ahhhhhh, what is permaculture design?” Novice or pro, I hope this spotlight serves as a look-through into the world of permaculture that all levels of green thumb and friend of Earth may appreciate.

What is Permaculture Design?

The content and its application are so broad, it can be tempting to ramble. The word permaculture is a contraction of words “permanent” and “agriculture,” which gives us a hint. I like authors, Bloom and Boehnlein’s definition in their book “Permaculture for Home Landscapes, Your Community, and the Whole Earth.” It describes permaculture “… as meeting human needs through ecological and regenerative design.” This definition captures its core concept: design with awareness of our dynamic relationship with nature.

Oh boy! That’s a wide brush stroke! Let’s attempt to deconstruct…

Who Practices Permaculture?

Bill Mollison & David Holmgren on Permaculture Design

Some call Australian-born naturalists, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, the “fathers of permaculture.” Early interests blossomed into lifelong passions and careers in permaculture. They wrote pamphlets, books, trained and lectured on permaculture design. Their thought leadership reaches globally. Over time, fundamental tenets coalesced into a formal curriculum and a permaculture design course and certification (PDC) emerged (more on this later).

Permaculture One: A Perennial Agriculture for Human Settlements (Mollison) and Permaculture Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability (Holmgren) are essential reads for a self-directed crash course in permaculture design. I personally entered the rabbit hole here (and I’m fixin’ on stayin’ a while…) and recommend these books to anyone interested in learning more.

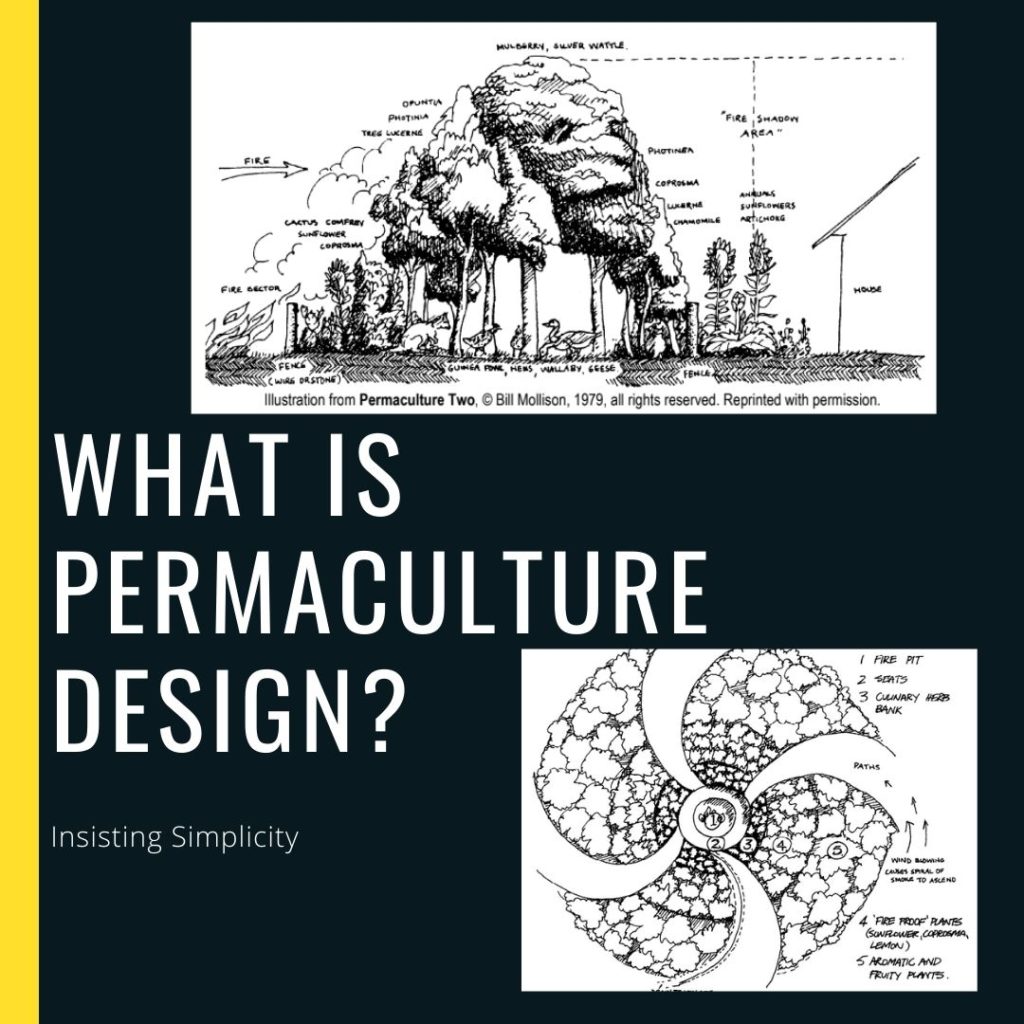

In differentiating permaculture from traditional agriculture, Mollison discusses the significance of design within the early pages of Permaculture Two: Practical Design for Town and Country in Permanent Agriculture:

If there is a single claim that I could make, in order to distinguish permaculture from other systems of agriculture, with the notable exception of keyline concepts, it is that permaculture is primarily a consciously designed agricultural system.

The main reasons for designing a plant system are:

– to save our energies in the system;

– to cope with energies entering the system from outside (sun, wind, fire);

– to arrange plants so that they assist the health and survival of other plants;

– to place all units (plants, earthworks and artifacts such as houses) in the best possible arrangement in landscape;

– to suit climate and site (specific design);

– to integrate with man and society, and save heating fuel and cooking energy; and

– to provide a wide range of necssities for man, in a way every man can achieve.

Permaculture design is deliberate, executed in concert with nature. To define it as “organic farming” alone would be incomplete.

Masanobu Fukuoka

Masanobu Fukuoka’s One Straw Revolution is a masterpiece. It’s no wonder why Mollison and other naturalists quote from it in reverence.

Artfully written, witty and informative on the topic of “natural farming,” Fukuoka made waves for his unconventional, passive approach. Peers didn’t share his enthusiasm:

But this was too much, or too little, for the everyday world to conceive. There was no communication whatsoever. I could only think of this concept of non-usefulness as being of great benefit to the world, and particularly the present world which is moving so rapidly in the opposite direction. I actually wandered about with the intention of spreading the word throughout the whole country. The outcome was that wherever I went I was ignored as an eccentric. So I returned to my father’s farm in the country.

My father was growing tangerines at that time and I moved into a hut on the mountain and began to live a very simple, primitive life. I thought that if here, as a farmer of citrus and grain, I could actually demonstrate my realization, the world would recognize its truth. Instead of offering a hundred explanations, would not practicing this philosophy be the best way? My method of “do-nothing” … farming began with this thought. It was in the 13th year of the present emperor’s reign, 1938.

Fukuoka’s writing style is simple and elegent, requiring no garnish. Elaborating on the “Do-nothing farmer:”

For thirty years I lived only in my farming and had little contact with people outside my own community. During those years I was heading in a straight line toward a “do-nothing” agricultural method. The usual way to go about developing a method is to ask “How about trying this?” or “How about trying that?” bringing in a variety of techniques one upon the other. This is modern agriculture and it only results in making the farmer busier.

My way was opposite. I was aiming at a pleasant, natural way of farming [Farming as simply as possible within and in cooperation with the natural environment, rather than the modern approach of applying increasingly complex techniques to remake nature entirely for the benefit of human beings] which results in making the work easier instead of harder. “How about not doing this? How about not doing that?” – that was my way of thinking. I ultimately reached the conclusion that there was no need to plow, no need to apply fertilizer, no need to make compost, no need to use insecticide. When you get right down to it, there are few agricultural practices that are really necessary.

The reason that man’s improved techniques seem to be necessary is that the natural balance has been so badly upset beforehand by those same techniques that the land has become dependent on them.

A powerful message. He advocates a simpler, less active, less technology dependent, less input dependent approach to cultivation. Viewed as backward and ignorant by his fellow farmers, Fukuoka held firm in a belief that a natural, simple method which seeks to facilitate not dominate nature is best.

Fukuoka’s four principles (which he writes in all CAPS, so I will too):

- NO CULTIVATION (plowing)

- NO CHEMICAL FERTILIZER OR PREPARED COMPOST

- NO WEEDING BY TILLAGE OR HERBICIDES

- NO DEPENDENCE ON CHEMICALS

One Straw Revolution holds a spot next to Thoreau’s Walden on my mental book shelf.

Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture

Sepp Holzer, the Austrian-born “Rebel Farmer,” got his name for practicing unconventional farming techniques. His deeds, at times, pitted him in opposition with local authorities and agricultural organizations. The nickname stuck and found its way into the title of his first book: Sepp Holzer: The Rebel Farmer.

I’ll reserve commentary to his second book, published about a decade later called: Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture: A Practical Guide to Small-Scale, Integrative Farming and Gardening. Someone told Sepp to pack a bit more in the title on the second go around!

The book describes techniques employed on his high-altitude Austrian homestead called: the Krameterhof. Diagrams, pictures and instructionals fill its pages, from plant guilds to raised bed design. It’s a great resource.

On his permaculture approach, Holzer states:

My methods have had over 40 years to develop. I have had time to continually improve upon and develop them so that now I have as little work to do as possible and I still achieve good yields. It was obvious to me that I was doing this by imitating natural cycles. What aspect of nature could I improve upon when nature already functions perfectly?

For Holzer, the basic principles of permaculture are:

– All of the elements within a system interact with each other.

– Multifunctionality: every element fulfils multiple functions and every function is performed by multiple elements

– Use energy practically and efficiently, work with reneable energy.

– Use natural resources

– Intensive systems in a small area.

-Utilise and shape natural processes and cycles.

– Support and use edge effects (creating highly productive small-scale structures).

– Diversity instead of monoculture.

Sepp Holzer’s Permaculture provides lots of practical take-aways, but a few are unique. The high elevation of the krameterof (~3,500 – 5,000 ft. above sea level) necessitates creativity. Holzer is a wizard with terrace construction. He discusses proper build technique to mitigate erosion/slide risk. He details which varieties of plants, shrubs and trees are best suited where, while explaining the importance of “microclimates.” It is via microclimates that Holzer can cultivate varieties that would otherwise be unsuitable.

Holzer gives practical advice on how to make a living with permaculture. He is the embodiment of a “successful unconventional farmer,” which may contrast with the miserly existence some picture when introduced to permaculture.

Related: Experiments in Urban Gardening

Where Can I Find Permaculture Design Online?

Tenth Acre Farm

Amy, author of The Suburban Micro-Farm: Modern Solutions for Busy People, runs a blog at www.tenthacrefarm.com, where she applies permaculture concepts to small-scale residential spaces. It’s an amazing resource if you’re into gardening and may be interested in experimenting with permaculture techniques. Amy is based out of Cincinnati and active in her community and greater region. Her recent blogpost on urban food forests (hey, I like those!) inspired this post. Thanks, Amy!

Practical Self-Reliance

Ashley runs a (truly badass) blog at www.practicalselfreliance.com, where she talks living off-grid and homesteading. She has tons of tips and amazing recipes. I guarantee a few minutes perusing her blog will generate a dozen ideas to try out! Ashley leverages her experience living in rural Vermont to contstruct well-researched posts with beautiful pictures. Keep rockin’, Ashley! Thank you for all of the great ideas already!

What Are Permaculture Ethics?

While Mollison and Holmgren may be dubbed the patriarchs of permaculture design, there’s no such thing as the “permaculture police.” No person, nor group have authority to declare what kind of agriculture is and is not permaculture. The folks mentioned above have many commonalities, but they’re individuals with unique voices. A permaculture seal of approval is somewhat missing the point. I mean, one guy calls himself the “Rebel Farmer!”

Permaculture design is experiential. It is site-specific. It is learned by doing, so don’t just read about it, go do it…

With that disclaimer, Bill Mollison began training people in permaculture design in the 1980’s, issuing a “certificate of completion.” This model serves as the basis for the modern-day Permaculture Design Course (PDC) Certificate, issued by various permaculture organizations globally. Typically, these are intensive on-site seminars. I have not participated in a PDC (but I’d like to someday!) and I do not want to give the impression that I’m endorsing any individual organization, so I’ll leave it at that.

Now that we’ve got two disclaimers on the table, permaculturists often couch their message within a permaculture ethic, which is three-fold:

Earth care, People care, Fair share

In the “Essence of Permaculture,” a summary of concepts extracted from David Holmgren’s Permaculture Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability, Holgren explains the permaculture ethic:

– Care for the earth (husband soil, forests and water)

– Care for people (look after self, kin and community)

– Fair share (set limits to consumption and reproduction, and redistribute surplus).

These are distilled from research into community ethics, as adopted by older religious cultures and modern cooperative groups. The third ethic, and even the second, can be seen as derived from the first. The ethics have been taught and used as simple and relatively unquestioned ethical foundations for permaculture design within the movement and within the wider “global nation” of like-minded people. More broadly, they can be seen as common to all traditional “cultures of place” that have connected people to land and nature through history, with the notable exception of modern industrial societies. This focus in permaculture on learning from indigenous, tribal and cultures of place is based on the evidence that these cultures have existed in relative balance with their environment, and survived for longer than any of our more recent experiments in civilization.

The permaculture ethic provides the why behind the techniques, while connecting something as simple as backyard gardening with a larger, loftier message.

Closing Thoughts on Permaculture Design…

For you folks with a bit of experience in gardening, I hope this spotlight on permaculture design gives you some ideas and points you in the right direction of additional permaculture resources. If you’re a total newbie, I hope this lit a permaculture spark! Now go get your hands dirty…

What are your favorite books on permaculture?

A pleasure to read this post, thanks !

Glad you liked it!